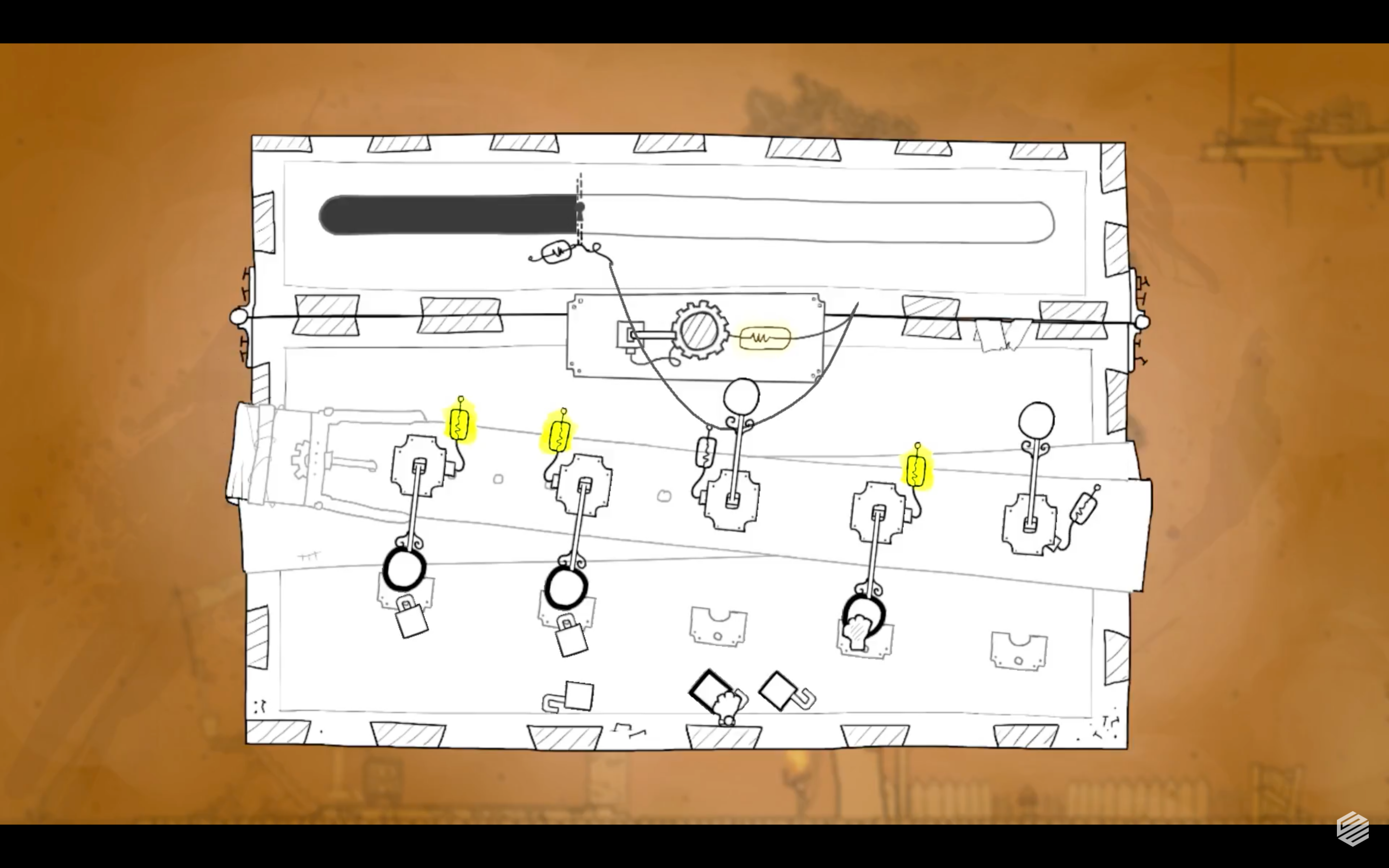

Games are full of problems that players need to solve. In the field of psychology, problems can be categorised into non-insight and insight problems. Most puzzle games feature non-insight problems, making players perform a series of actions before solving the puzzle. “Non-insight problems are designed to be solvable through a process of systematic application of knowledge and logical deduction”, explains Margaret Webb in Frontiers in Psychology (2016). 39 Days to Mars (It’s Anecdotal, 2018), for example, includes a puzzle in which players need to flip specific switches until they have filled a gauge by a certain amount (Figure 1). Players thus need to work their way to the goal to solve this type of problem. This is known as “hill climbing” in problem-solving and mathematics and means that problem solvers approach a solution gradually, sometimes through trial and error at each step (Johnson, 2011).

Insight problems, on the other hand, do not require players to complete a series of actions to be solved. “Insight or Aha is often identified as the subjectively distinct feeling of sudden and unexpected understanding that may accompany attempts to solve a problem”, states Webb (2016). This type of problem can be encountered in all game genres, as grasping mechanics, deciphering patterns or developing successful tactics may be equivalent to insight problems in games.

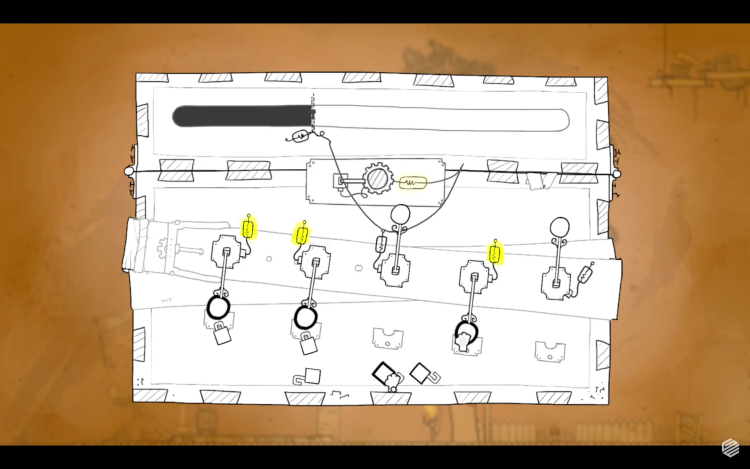

It appears that insight problems are occasionally solved for players in the form of tutorials and user interface. Patterns, such as enemy weaknesses or crafting mechanics are often extensively explained (Figure 2), possibly because some games would rather focus players on moments of high-intensity combat or exploration instead of problem-solving. It could be argued that tutorials lower player agency or, conversely, that they reinforce feelings of immediacy and thus strengthen certain games.